- Gathering Note

- Posts

- Seattle Opera’s Rheingold a triumph, with strong cast and ingenious staging

Seattle Opera’s Rheingold a triumph, with strong cast and ingenious staging

The gods Froh (Viktor Antipenko), Freia (Katie Van Kooten), Donner (Michael Chioldi), Wotan (Greer Grimsley), and Fricka (Melody Wilson) in Das Rheingold at Seattle Opera. © Philip Newton.

Review published on Seen and Heard International

Not long ago, staging Das Rheingold at the Seattle Opera usually meant that the other three operas in Richard Wagner’s Ring Cycle would soon follow. The company was once a Wagnerian destination in the U.S., though not on the same level as the renowned Bayreuth. For decades, when the lights dimmed and the famous chord of E-flat major emerged from the orchestra, slowly at first and then transforming into the flowing Rhine, Seattle audiences and visitors from around the world settled in for a cycle-full of leitmotifs.

That was then. Seattle audiences have not seen Rheingold in ten years. This concise story of power, hubris and consequence is a fanciful two-and-a-half hours of gods and giants; castles and contracts; and of course a subterranean bad guy with an ax to grind. Rheingold sets the whole Ring Cycle in motion, its story serving as the seed of the original sin growing through Wagner’s ambitious four-part drama. But even staged alone – as it was here – there is much to enjoy in this tale of mythic gods with human failings.

This year’s production of Rheingold was conceived by Brian Staufenbiel and first staged by the Minnesota Opera in 2016. A notable feature is the placement of the orchestra on the stage instead of the pit. It’s a feature born of necessity: The Minnesota Opera’s pit is too small for the full-sized ensemble demanded by Wagner. Staufenbiel’s fix was to place the orchestra at the center of the stage amid the action. At first, I was skeptical that such a change could work. But the deeper into Rheingold we got, the more I was convinced that it was a well-made choice. The orchestra, with its size and near-constant churn of Wagnerian leitmotifs, is as much a character in the opera as Wotan, Loge, and Alberich. Ludovic Morlot and the Seattle Symphony were expressive, colorful, and always supportive of the singers on stage. And the freed-up pit was dragooned as a slightly recessed Rhine and – later – the mines of Alberich’s underground realm.

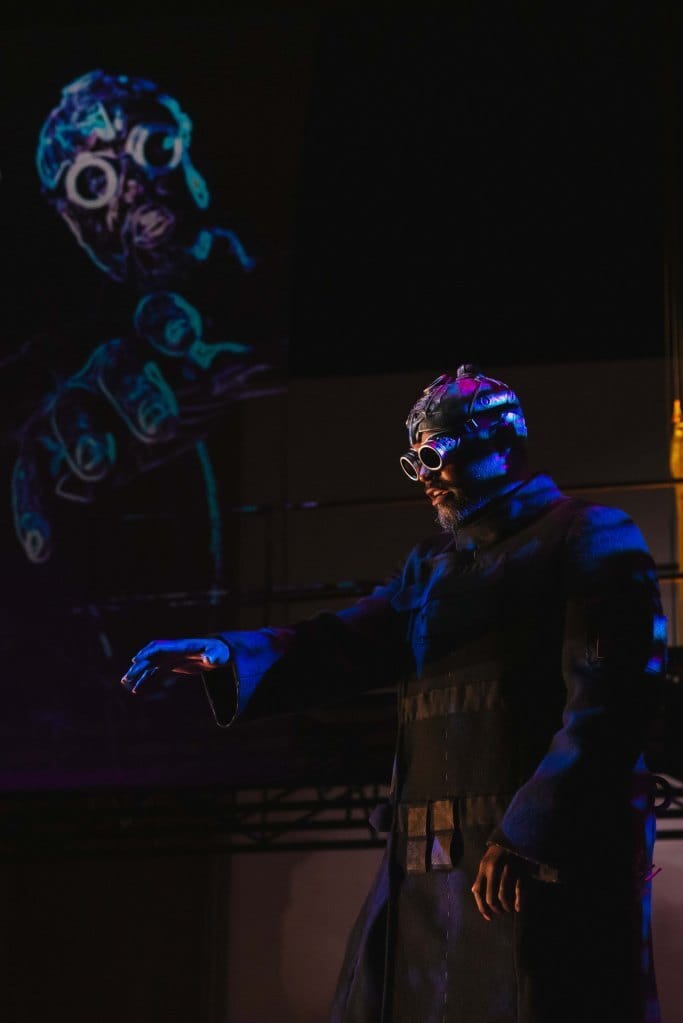

Frederick Ballentine as Loge, Michael Mayes as Alberich, and Greer Grimsley as Wotan in Das Rheingold at Seattle Opera. © Philip Newton

Screens, projections and scaffolding do the bulk of the place setting for the opera. Seattle Opera has long relied on its state-of-the-art projection system, but I can’t recall a production that used the technology as effectively as this one. The technology is employed to particular effect to make the giants Fafner (Kenneth Kellogg) and Fasolt (Peixin Chen) larger than life via discreetly placed cameras that project their facial expressions high above the stage. Other projections conveyed a flowing Rhine and the majestic castle Valhalla. Scaffolding running the length of the stage helped set the gods apart from everyone else, until Wotan (Greer Grimsley) and Loge (Frederick Ballentine) venture to the realm of the Nibelungen.

Kenneth Kellogg as Fafner © Sunny Martini

Greer Grimsley anchors a generally strong cast. Grimsley is no stranger to Seattle and Wotan. To my ears, his 2023 Wotan is more sober and world-weary compared to the last time I heard him perform in the Seattle Opera’s 2009 Ring Cycle. Ballentine’s dexterous, lighter tenor is perfect for the opaque Loge. Alberich is given a biting, degenerate performance by Michael Mayes, while Martin Bakari is strong as a sympathetic Mime. Chen and Kellogg sang Fasolt and Fafner with thundering abandon.

Others in the cast added their own confident performances including Katie Van Kooten as Freia, Melody Wilson as Fricka, Michael Chioldi as Donner, Viktor Antipenko as Froh and the trio of Rhinemaidens sung by Sarah Larsen, Jacqueline Piccolino, and Shelly Traverse. Only Denyce Graves, making her Seattle Opera debut and singing the role of Erda, was a disappointment. On opening night at least, her voice sounded strained in a few parts as she tried to convey her warning to Wotan with seriousness.

Staufenbiel’s Rheingold will hopefully be remembered long after its run with the Seattle Opera ends. It is simple without feeling cheap, demonstrating the artistic possibilities of even limited budgets. The company continues to show an uncanny ability to cast Wagner’s operas with established stars and singers on the rise. And with the Seattle Symphony in the pit – or in this case, onstage – there is much to hear. Few orchestras in the United States are as gifted in this music.

General Director Christina Scheppelmann has been careful to remind patrons that a full Ring Cycle is not coming soon. But so much went right with this Rheingold that I hope it inspires an effort to bring a new Ring to Seattle before too long.