- Gathering Note

- Posts

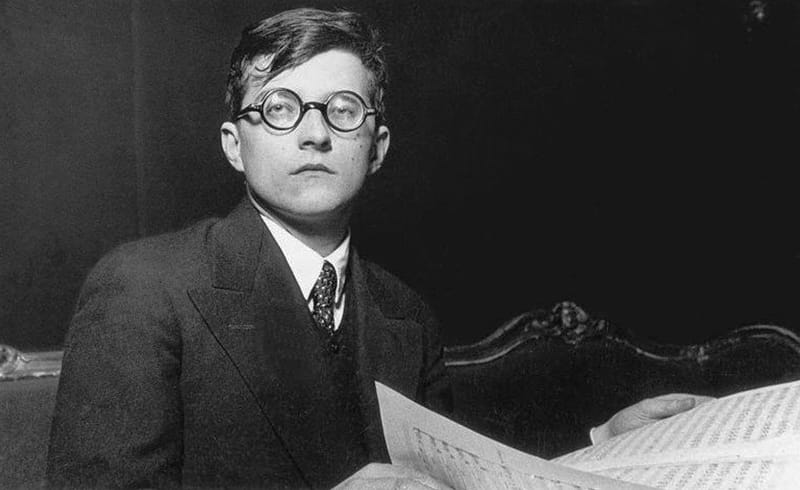

- Klaus Mäkelä meets Shostakovich

Klaus Mäkelä meets Shostakovich

The election last week has been, to put it mildly, numbing. I made it through about a year of the first Trump administration before the despair set in. It was the Jesuits—thank you, St. Joseph and Seattle University—who helped keep my soul intact, offering me a lifeline of reflection and community. And, surprisingly, Leif Ove Andsnes’ Sibelius recital album also played its part.

Sibelius’ piano music often feels elusive, overshadowed by his more imposing symphonic works. It doesn’t thunder at the heavens or demand your attention—it lingers somewhere in between. At the time, Andsnes’ recording of these pieces felt like a lifeline. His tonal shading, his gentle yet precise touch, invited the introspection I needed to find my way to a healthier mental place.

My self-care plan in the event of another Trump presidency was always going to involve a lot of music. I know how therapeutic it can be during turbulent times. However, I didn’t fully appreciate how quickly it would be needed as the immediate aftermath of the election began to unfold and the news cycles became overwhelming.

Even before the election, I had been spending time with Klaus Mäkelä’s new two-CD recording of Shostakovich’s 4th, 5th, and 6th symphonies. First things first, I am not a Mäkelä hater. I don’t believe as some do that to be a great conductor your numeric age must begin with an eight.

When Ludovic Morlot became music director in Seattle, most of Seattle’s classical music community was ready for a change after the lengthy tenure of Gerard Schwarz. It didn’t matter to most that Morlot, because of his youth, didn’t have an established record in the core European repertoire. When Morlot debuted as music director with a program that included the Eroica Symphony and two pieces by Frank Zappa, we were more than willing to follow his lead. That first performance of the Eroica was clean, detailed, and sharply played. I marveled at the cohesion of the Seattle Symphony, which wasn’t always a trait found in Schwarz’s performances. But for all of the virtues, it lacked heroic gestures and profundity. As the years have gone on, Morlot’s performances of the Eroica have gotten better and better. He still conducts transparent performances, but over time, he has taken more liberties with phrasing, dynamics, and tempo to make his points.

Mäkelä may not get the same long leash in Chicago Morlot had in Seattle. Now that I am in Chicago, I am genuinely interested in how he will “do” with the Chicago Symphony when he becomes music director in 2027. Next year I will hopefully be able to hear him conduct Mahler’s Third Symphony (my favorite) and Dvorak’s brooding Seventh Symphony. Until then, I am left trying to understand Mäkelä through his recordings which I have dutifully collected.

I thought his Sibelius cycle was drab in its effect, but not terrible either; it had moments of genuine beauty amidst an overall mannered approach. In certain passages, the subtleties he brings forth can be quite striking. However, he perhaps focuses a little too much on the details to the detriment of the overall direction Sibelius has in mind for each symphony, sometimes sidelining the music’s sweeping grandeur. This tendency can occasionally lead to a lack of cohesion in the broader narrative that Sibelius masterfully constructs. Despite this, I’ve enjoyed each recording Mäkelä has released. They offer glimpses of brilliance. His interpretations invite the listener to engage with the music from fresh perspectives.

By contrast, his latest work with Shostakovich feels different in several ways. We’ve been weaned on the idea of Shostakovich as the quintessential subversive artist, who embeds intricate political messaging into his works as a pointed critique of the oppressive Soviet regime. This historical lens has shaped the way we listen to and interpret his music over the decades. I get that listeners have come to expect Shostakovich performances that are wrenching, filled with emotional turmoil and stark contrasts, but why should that be our only expectation?

There is a superficiality that pervades these performances that encourages a rethink of these masterpieces. Shostakovich himself, brimming with youthful ideas, was only in his late twenties and early thirties when he composed these remarkable symphonies. Shostakovich at this time, like Mäkelä now, is still a work in progress. Mäkelä’s Fifth doesn’t really wallop the way it could, lacking the visceral impact and emotional crescendo, and the Fourth sounds overly managed, almost overthought, as if Mäkelä felt compelled to adopt a different point of view—somewhere—amid this trio of works; meanwhile, the Sixth skips along oblivious to the world, as though it were blissfully unaware of the tensions and struggles coursing through artistic communities in the USSR at the time.

In a reinterpretation that’s equal parts clarity and complexity, Mäkelä pushes us toward a subtler understanding of Shostakovich’s intentions, peeling back layers blurred by conventional performance choices. His reading of the Fourth Symphony aims at a cohesive listening experience, smoothing out its more abrasive edges, while the Fifth, though softer in its crescendos, leaves an impression of grandeur and stateliness. It’s not the Shostakovich we expect but the performance feels less like a misstep than a fresh lens.

It’s almost as if Mäkelä mirrors Shostakovich’s own tightrope walk. Shostakovich composed a symphony that would pass the censors. This is done without waving any red flags. Mäkelä’s approach, too, is one of restraint—an interpretation so free of subversive bite that it almost adds one. It’s a performance whose sincerity feels disingenuously genuine, offering a kind of double-edge to the music that speaks to the political gamesmanship embedded in Shostakovich’s work.

Mäkelä’s Shostakovich recording offers a path through our own ambivalent times. There’s something fitting, almost fated, about a Shostakovich symphony that sounds restrained and conflicted. Just as we live through a moment of tense facades, so too does this music feel like it’s speaking under the breath, holding back as much as it says. And perhaps that’s why this album feels timely, even necessary.